Tagging Porbeagle Sharks with One Breath // #FullSignal

2025-10-06

Tagging Porbeagle Sharks with One Breath // #FullSignal

For the first time, French and German scientists have tagged one of Europe’s most elusive predators without ever having to catch it.

est. reading time: 8-10 minutes

Using freediving techniques, the team deployed an acoustic transmitter on a porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus) – a species possibly recovering from the brink of extinction. Field scientist Lukas Müller shares what the moment revealed about shark tagging approaches and the return of a forgotten shark.

Signal: Shark in the mist.

“My safety diver, Lennart Vossgaetter, came up ascending from the dark planktonic mist… signaling shark. This was the moment we had all been waiting for.

What was going to be a rather short dive on a single breath of air felt like one of the longest dives I’ve had in the field.”

The team had gone the first four days of their expedition without a confirmed sighting. Visibility was low, while the dive computer read 15°C water temperature. After four hours of staring into the darkness, suddenly, one safety diver surfaced with the agreed-upon signal.

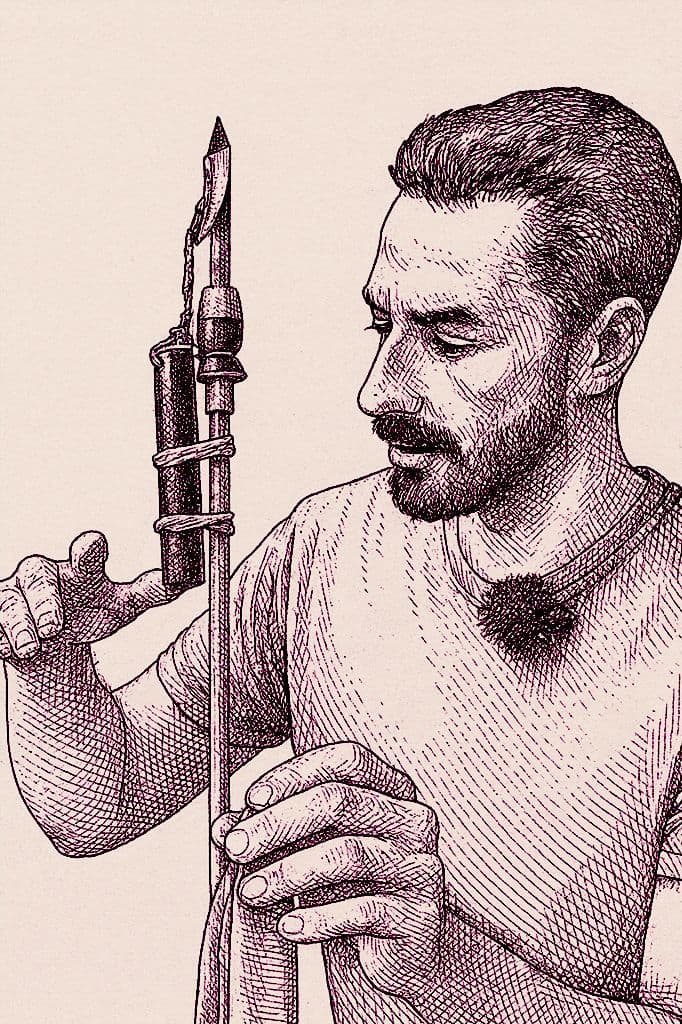

Lukas Müller took a deep breath. He carried a special tagging gun as he descended. This was the team's first opportunity to tag one of Europe's most endangered shark species with an acoustic transmitter.

“As I descended, I could already see the shark circling beneath me.

I had to wait — just long enough for the angle to be right, for the animal to trust me enough to get close. Staring at me from an armslength away was a porbeagle shark. I aimed. It was all happening in slow motion.”

When Citizen Scientists and Experts Meet in the Field.

To support elasmobranch research projects in Europe, trained shark researcher Lukas Müller founded the Ocean Collective together with three colleagues.

“We understand ourselves more as a field team facilitating field capacity as field technicians — really focusing specialized techniques in shark telemetry or advanced drone aerial surveillance. Citizens join our expeditions which allows us to get to work in meaningful ways.”

The company operates outside traditional structures, but always in close collaboration with local institutional and academic partners. In this case, the porbeagle project was initiated by Dr. Armelle Jung, Arthur Ory, and the French NGO Des Requins et Des Hommes. Their work builds on four years of free-diving-based shark observation and individual photo identification.

From the start, the aim was to design methodologies that fit both scientific objectives and the ethical and logistical realities of studying an endangered shark species in the densely used waters of Brittany’s coastline. Their challenging October outings marked the first joint mission to tag a porbeagle sharks using freediving techniques as part of DRDH’s and OC’s collaborative acoutic telemetry project.

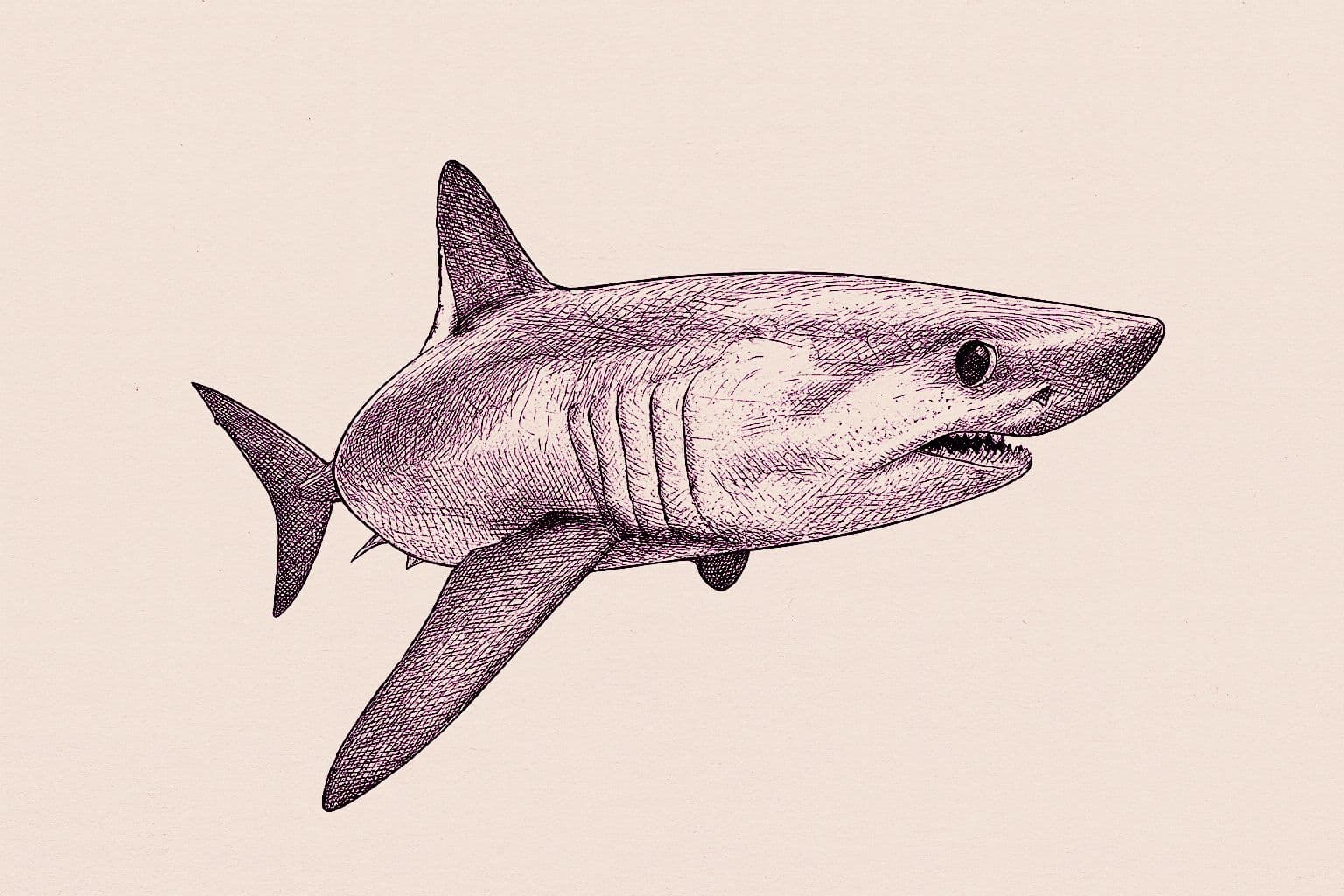

The Porbeagle Puzzle.

Porbeagle sharks (Lamna nasus) are classified as critically endangered in European waters. Across large swatchs of their historic home ranges, they have not been seen for decades.

Until the mid 20th century, porbeagle sharks were still relatively common in the Northeast Atlantic. Historical fishery records show regular landings in ports along western France and northern Spain, often as bycatch in bottom longlines or gillnets.

In his 1977 field notes, marine ecologist Jacques Nouvel described seeing “porbeagles cut up on docks for meat like any other fish” in Brittany’s Finistère region. While not targeted in the same way as bluefin tuna, porbeagles were considered a commercially useful species, prized for their meat and liver oil.

A brief but intense period of targeted fishing began in 1961 when Norwegian and Faroese vessels launched dedicated porbeagle operations off the British Isles. Landings peaked and collapsed within five years, a pattern echoed later in the Bay of Biscay and North Atlantic, where French and Spanish longliners continued to take porbeagles through the 1990s and early 2000s.

By 2008, ICES estimated that North Atlantic populations had declined by over 90 percent from historical baselines. An EU-wide catch ban followed only in 2010. Due to their slow growth, late maturity between 12 and 18 years, and low reproductive rate, porbeagles remain at risk, with recovery expected to take decades even under ideal protections.

In the waters of his home country, Müller notes, the situation is particularly stark.

“At a maximum length of over three meters porbeagle was once considered Germany’s largest predator. It has completely vanished from our waters.”

This makes the characterisation of an aggregation site of porbeagle sharks off the coast of Brittany by the French team particularly significant. Using photogrammetry and biopsy-sampling while freediving, DRDH has compiled a catalogueof over 130 individuals between 2021 and 2023. All sighted sharks had been females, 19 of which have been resighted up to four consecutive years.

While the aggregation site in Brittany has shown consistent returns of sharks during the summer, the wider picture remains fragmented: In Irish waters, satellite tags have traced individuals on migrations spanning thousands of kilometers, revealing seasonal routes that stretch from the Bay of Biscay to the Azores and up toward the North Sea. Additional efforts in Norway, Ireland and the UK aim to define stock structure and habitat use. But taken together, these efforts still form an incomplete map. The porbeagle's recovery story is unfolding with individual chapters in search of the common thread.

However, research teams attempting to study endangered species always face one important question: How to collect meaningful data without compromising the wellbeing of a population already under pressure?

Method Matters: Catch or Freedive?

There is no single correct method for tagging sharks. Decisions depend on animal behavior, habitat conditions, project goals, and team capacity. In porbeagle research, two approaches are most often considered: traditional catch-based tagging and freedive-based external placement.

“Your tagging approach should always be guided by ethical considerations – of whether this work is safe for the anima and crew. And within the context of proportionality for its potential conservation and management benefit. Of course, every scientist will tell you that budget contraints, regulations, and stakeholder settings quickly add additional complexity long before our tags hit the water.”

For this project, the team decided in favour of a free-diving method, which was developed in close cooperation with the French partners. The porbeagles were to be tagged with externally mounted acoustic transmitters. The decision was not about rejecting the alternative in principle, but about choosing the best possible method in terms of the environment, ongoing projects and ethical thresholds.

“I believe that there is not one ‘best’ method. Instead, it really depends on what is the goal of the study, what is the species, what are the local field conditions, what is the capacity and capability of the team, what are our budgets, and what is the necessary threshold of data that we need in order to even justify conducting a study like that in the first place. While there are certainly studies that are extremely conservative - yet not producing data of significant value to conservation, there are also studies that accept mortalities of a subset of their tagged individuals in order to answer questions that are critical for responsible management.”

Here’s how the team framed the options:

Traditional Catch-and-Tag Method

Benefits:

- Physical access allows:Blood sampling, genetic & muscle tissue extraction, ultrasound, measurements

- Longer contact enables surgical tag insertion (e.g. internal acoustic tags)

- Easier to ensure tag placement accuracy & longer retention times

Trade-Offs:

- May cause significant stress to the animal

- Risk of injury or mortality - especially with sensitive species

- Logistically demanding (requires boat rigging, gear, trained team)

- Funding intensive & dependent on stakeholder setting

Freedive-Based Tagging

Benefits:

- No capture or handling required

- Lower physical disturbance and therefore lower mortality rates

- Suited for large or difficult-to-catch species

- Cost-efficient, especially in remote or logistically locations

Trade-Offs:

- Limited to external tag placement

- Shorter tag-retention times

- No holistic blood/tissue/ultrasound sampling possible in a single work-up

- Requires strong field experience in freediving

Tagged, toasted, and then: another premiere.

The team’s first successful tagging process lasted only a few seconds. The HP-16 tag – customized for this project – was reinforced with Dyneema line and secured using a benign metal anchor, designed to sit just beneath the skin and be expelled after a few years. The position just below the dorsal fin allowed clean deployment.

“After some high-fives, we put our masks back in the water. The shark had come back and was circling again. The perfect opportunity for us to shoot photos and videos for sex identificaiton and size estimations.”

A few hours and one alleged bottle of Cotes-Du-Rhones later the team discovered that the tagged shark had in fact been the first male shark ever documented at this field site.Until then, every confirmed porbeagle had been female. DRDH and OC have continued their collaborative field work since:

“We have returned with more field time this year and have been able to tag one of the most important females of the ID catalouge. This 2.6 meter long female has been spotted in Brittany four years in a row and was probably gravid at the time of tagging."

Together with the French collaborators, the team now hopes to build out a longer-term acoustic monitoring effort in the region. The goal: to track porbeagle movement patterns and uncover whether this site a seasonal aggregation, of reproductive importance, or part of much larger porbeagle puzzle.

First Pings, Future Patterns

For porbeagle sharks in the North Atlantic, key questions remain unanswered:

Where do adult females pup? Where do juveniles spend their first years of life? And what role do marine protected areas (MPAs) play in shaping aggregations?

“As I have learned from my French colleagues ‘For every answer these porbeagles give us, they pose two new questions.If the large suspected pregnant females are leaving the area, where are they going to pup? Could it potentially be waters in the UK where there's reported sightings of juveniles? Could it be in the Bay of Biscay where we have sighted juvenile porbeagles multiple years in a row? Despite this uncertainty, it’s exciting to see this critically endangered species return from the brink.”

The collaborative telemetry project now underway is not positioned to answer all these questions alone. But by building a long-term acoustic array in Brittany’s aggregation site and tagging its locally known porbeagles, the team hopes to contribute one critical puzzle piece.

“Vive le requin taupe.”

🔬 Explore Tag Builder

Curious how to design your own tagging study? Visit Tag Builder to explore telemetry options tailored to your research goals.

👩🔬 Follow Researcher's Work

Lukas Müller is a shark scientist and co-founder of Ocean Collective. He is combining freediving techniques and citizen science expeditions to unlock research capacity to study endangered shark species.